(In “The scenographer”, 2007)

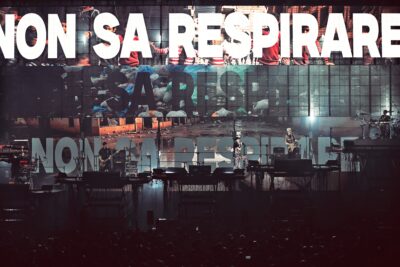

Canadian-born Robert Lepage is one of the most acclaimed directors and interpreters of contemporary theatre. Together with the stage designer Carl Fillon and with the technical staff of his multimedia team Ex Machina, based in Quebec City he has planned and given life to some of the most emblematic examples of the dramaturgical use of scenography as well as the technique and integration of video onstage.

THE ANDERSEN PROJECT

The story-line

The story’s main character is Frederic Lapoint, successful lyricist for rock singers, an albino from Montreal in the throws of an emotional crisis following a temporary separation from his wife, who is commissioned by the Opéra Garnier in Paris to rewrite Andersen’s fairy tale, “The Dryad”. It is the fable of a woodnymph that lives in the hollow of a tree and who renounces immortality in order to visit Paris for a day.

The person who called him, in fact, aims to produce a children’s musical. The other lead is the French manager who has to organise the event; extremely busy and always tied up in lengthy phone calls, who is obsessed with sex, which he satisfies by frequenting a red-light club run by a Moroccan graffiti artist, Rashid. Hans Christian Andersen in person also comes on the scene, with his passion for travelling and his unrequited love for Jenny Lind. In addition to being based on “The Dryad”, reference is also made to another Andersen fairy tale, “The Shadow”.

All the characters, interpreted by the eclectic Lepage, coexist with a shadow that reveals not only their interior personality and ideal aspirations but also their material objectives and sexual deviations. A shadow that, if left unfettered, as in Andersen’s tale, can lead to personal ruin. Frederic arrives in Paris full of hope but will remain disappointed; the manager is abandoned by his wife, while Rashid freely roams the Metrò to let loose with his spray can.

The set like a giant eyeball

For The Andersen Project Lepage and the young Le Bourdier on his first theatrical stage design project, having previously collaborated with Ex Machina by designing the sets for the film version of The Far Side of the Moon, together invent a decidedly original scenic structure, pulling references from Baroque stagecraft and demonstrating how it is possible to achieve the same perceptive illusion of virtual reality by using a combination of traditional craft techniques and optical effects.

For the show Lepage creates a scenario comprising various levels of depth and action (as already experimented in The Seven Streams of the River Ota) in order to vividly recreate a period such as the late nineteenth century, so full of technical and scientific discovery; he attempts to theatrically recreate the effect of astonishment and wonder universally experienced by the new optical devices. Great use of depth is made, with the stage area blocked into different areas of action corresponding to as many scenic mechanisms within a framework, which enables the “tricks” (the machinery and the runners) to be concealed beneath the stage area and in the wings.

To the rear is a large cubic volume in perspective, a “panorama” (called “the landscape” by the technical crew) covered in a special cloth which, thanks to a pneumatic system, can either cling to the interior of its walls or can expand towards the exterior thereby distorting the image projected frontally onto its surface to give the effect of a shell or an eyeball. The magic of this technique enables a mechanised and efficient integration of body and image (thanks to a slight raising of the central part of the structure), restoring the illusion of depth, or rather, a false 3D, with an invisible and rapid transition from one state to another (concavity-convexity); the moving back and forth of the entire panorama on tracks creates an additional depth of field to the stage area.

The concept of threedimensionality, as we know, is linked to stereoscopy: we have two eyes and we perceive the threedimensionality of objects. We see one image but one eye views it differently from the other. After all, virtual reality is based on this three-dimensional perception, in that it makes a pair of eyes see two different images. Here, the perspective, manipulated much in the way that is characteristic of seventeenth-century stage design “loses its illusionist character and starts to become the instrument of identification between real space and the scenic space” (F.Marotti).

The genesis of the work: Hans Christian Robert?

As Robert Lepage himself admits, The Andersen Project represents a ‘sum’ of all his work, not just the socalled one-man shows. In fact, here again we find the themes of solitude, of abandonment, incommunicability, of unsatisfied sexuality and romantic tension for a love or for a renown that is not realized, already present in Needles and Opium, Vinci, The Far Side of the Moon, and Elsinore; but we also recognize the figure of the independent artist, free of the imperatives of the art market, as touched upon in Vinci and Busker’s Opera; and the technical and visual solutions previously used in The Seven Streams of the River Ota. The recurring biographical theme is that of the renowned artist, as in Vinci (Leonardo), La casa azul (Frida Kalho/Diego Rivera) and Needles and Opium (Jean Cocteau and Miles Davis), to which the contemporary character compares himself.

The Danish author of children’s literature is thus backlit and visible through the lives of contemporary characters who find themselves faced with personal choices in part similar, though a century later. The central figure becomes a kind of model before which the characters (mostly visual artists) love to face and examine themselves: Leonardo da Vinci (incarnating the union of art and technology) and Jean Cocteau (sublime example of artistic eclecticism) are among the topical themes in Lepage’s show, also in the form of iconographic citations or quotations from their works. The scenographic theme of the mirror image (or of the mirroring of characters) is an almost obsessive constant in Lepage’s shows and, according to the critic James Bunzli,would introduce an unequivocal autobiographical element: the character and hismanifold doubles would be none other than Lepage himself, who would speak of himself by literally creating a reflection of himself in their moral dilemmas, in their crises of love, their solitude, in their doubts on art and life.

In The Andersen Project Lepage in effect reveals a surprising affinity with the Danish author Andersen, not least in their sharing the same love for travel and an insatiable sexual desire. “The Life of a Storyteller” by Jackie Wullschlager and his diaries, made available by the show’s commissioners, The Andersen Foundation, reveal a wealth of information. They in fact unveil unknown facets in the life of the nineteenth-century author; and it is these aspects that the show hinges on: the double life that would be hidden behind Hans Christian Andersen’s romanticism, that will never have him marry his beloved Jenny Lind: “In the Romantic era men would write passionate letters to each other, yet it didn’t mean they wanted to sleep together; Andersen’s romanticism, though, went over the top and he wrote open love letters to a lot of young men. He also had great passions for a few women, although they were women he was pretty sure it would be impossible to love – Jenny Lind, for example, one of the great Swedish sopranos, whose touring schedule made a relationship out of the question. It was discovering that this man best known for writing children’s stories had a double life, a strange, troubled personal history, that made me agree to do a show about him”.

As Lepage himself points out, there are a number of points that his personality has in common with Andersen, other than a voracious sexual appetite: a troubled childhood, the question of language – always an underlying theme in his shows, inextricably linked with the fierce political arena of French Canadian separatism – and the quest for international recognition of his work: “It’s hard to talk about what Andersen and I have in common without sounding pretentious, but there’s a lot about him that I identify with – not least his insatiable sexual desire and constant mood of sensuousness. There is a connection between sexuality and creativity, and one of the themes in The Andersen Project is to do with the imaginative and sexual development of children. Reading fairytales to children expands their imaginations. As they grow older, they replace their bedtime stories with masturbation and sexual fantasy. I always worried that I was a sex maniac because I thought about sex all the time, but actually it’s part of the imaginative process. If you’re a storyteller and spend your time imagining things, your sexual imagination is likely to be just as vivid. Perhaps Andersen’s sexual uncertainty reflects his difficult childhood. It’s no coincidence that it was Andersen who wrote “The Ugly Duckling”, a metaphor for the awkwardness of childhood and the blossoming of adulthood. I can identify with this, too: where Andersen was tall and ungainly, I had alopecia. Both of us experienced how cruel children can be. That can be tough, but being put through the mill very young can also be an advantage because you don’t see the world in the same way. Another thing that connects us is the need to travel. A lot of artists in the 19th century felt that they had to travel outside their own country to be recognised. But Andersen felt he had more reason than most. First, he wrote in Danish, a language that, for a lot of people in Europe, was like speaking backwards. Second, he wrote for children, so he wasn’t taken seriously. To be recognised, he had to go Germany and France to mingle among the great writers of the day. He’d come back to Denmark with all of that recognition. If you are a Quebecois artist, as I am, you feel the same impulse. Even an English-Canadian feels he has to be approved by London, Paris or NewYork. But Andersen sometimes did things for thewrong reasons – just like the heroes in his stories”.

The theme of sexuality voluntarily repressed or experienced as a conflictual state would therefore be the core theme of the show: “My first idea for The Andersen Project was to do with masturbation. The theme came about not in a sleazy, crass way, but as a way of trying to understand Andersen. I don’t want to shock – I just want to show Andersen’s lucid vision of the human condition. And the theme makes extra sense because a solo show is the most solitary form of performance and masturbation is the most solitary form of sex!”.

Every solo show that Lepage stages deals with the main character’s solitude. Solitude that manifests itself in the painful search for a way out through the other or through self analysis. From Vinci to Tectonic Plates (Les Plaques tectoniques) the character undergoes an exterior and interior transformation throughout the course of the show, thanks to a salvificmirroring with his other self. A recurrent theme of all his shows is that of looking within oneself, of examining oneself in a way that we have never before seen, of understanding the anguish that assails us and the contradictions of our life in order to overcome them. The initial cause is always a rupture, of an emotional, psychological or moral nature; the social drama – declared Victor Turner – begins with a loss: the drama, read in a ritual and anthropological sense, is in fact, according to Turner, “part of a disharmonious process that arises out of a situation of conflict”. In “From Ritual to Theater: the Human Seriousness of Play” and in “The Anthropology of Performance”, Turner expounds on the theme of social drama, which occurs when in the course of a community’s daily life a break in the traditional rules of living is created, generating opposition, which in turn transforms into conflict.

In order to be resolved, this necessitates a critical reappraisal of particular aspects of the established, legitimate social-cultural order. Thus a rupture marks the beginning of the “social drama”, the crisis opens the way for the “dramaturgical phase”. All Lepage’s solo shows stemfroma deficiency, an imbalance, (in Greek, hamartia), from a bereavement (in Vinci, Philippe is spurred by the idea of travelling following the suicide of his friend Marc; in The Far Side of the Moon the two protagonists meet on the occasion of their mother’s death; in Needles and Opium, the protagonist experiences the anguish of being abandoned by his love), by a crime (Polygraph), by a marriage in crisis (The Andersen Project); in some cases such drama would hint at autobiographical episodes of an extreme and painful nature. The Far Side of the Moon was created soon after the death of Lepage’s mother, scenically associated with the image of the moon, universally a female symbol. Elsinore (Elseneur) was inspired more by the death of his own father than by Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Between Romanticism and Modernity: the triumph of technology

“The Dryad” was written on the occasion of Andersen’s visit to the Paris Expo of 1867, the year marked the death of Baudelaire, who had dedicated to modernity the essay entitled “Le Peintre de la Vie Moderne”. At the 1867 Expo important new technologies and improvements in already patented optical and mechanical instruments were presented, among which a great number of stereoscopic photographic items on display. The contrast between the characters in the show is precisely like the contrast between Romanticism and Modernism.

As Lepage explains: “The Universal Exposition of 1867 signifies the end of Parisian Romanticism and the dawn of Modernism. And in Modernism Andersen sees fairy tales, amazing machines, a masculine world, a realist, mathematical universe founded on objects that are very concrete … I may be accused of Romanticism in both my private and professional life, but these are recurring themes in my shows: the fact that romantic individuals find themselves in a very concrete world where there is little space for poetry, for excess, for passions”.

If we want to find an ulterior connection between Andersen and Lepage in terms of their common fascination with technology, we need only look at Montreal, Lepage’s homeland, which in 1967 hosted an international Expo where the Czech set designer Joseph Svoboda, in his country’s pavilion, demonstrated a multi-projection video installation that further developed on the polyécran system invented for the Prague Expo of 1958.