Abstract: In the first weeks of the quarantine due to the coronavirus, we were dedicating our online lessons to Hamlet when we realized that we were Hamlet in our Denmark-prison. An email dated 18 March inspired us: a video message by Bob Wilson himself that suggested us how to read our terrible time with Shakespeare and urged us to go on with three phrases pronounced by Hamlet. The first is the one with which he himself as actor opened his Hamlet a monologue in 1995: Had I but time -as this fell seargent Death is strict in his arrest- (repeated by the Prince of Denmark three times) and which corresponded to the final sentence of the tragedy, the second is that of Hamlet in letter for Ophelia Don’t doubt I love, the third is the one addressed to Horace when everything ended, The rest is silence. In this era of pandemic, when actions were taken untimely, it is right to ask ourselves what time we missed. And when there is nothing more to do, we ask that at least that the dead do not die alone. And in vain. Who will tell our story?

And in this harsh world draw your breath in pain To tell my story. (Hamlet)

Had I but time: these are the words that Hamlet pronounces before he dies and entrusts Horace with the task of telling his story. The looming death only allows him to become the protagonist of a tragedy of which Horace has been silent and helpless witness: he will have the hard task of explaining what time has been missed. There is no more time. Exactly what in this video nurses and doctors of the Infectives section of the Sacco hospital in Milan say: they are engaged in the front line in the battle against coronavirus.

There is no more time, we no longer have beds where people can be hospitalized, we are forced to reuse personal protection devices because they are scarce and in many situations those available are not suitable. We know that we risk contagion every day as well as experiencing the fear of bringing the virus into our homes “. (Milan, March 16, askanews)

Bob Wilson in his Hamlet in Monologue starts the tragedy with this same phrase Had I but time just some seconds before the protagonist’s death; the story being told has already happened: “It started just before he dies, and ended with his last speech. This one second before he dies, one sees the whole play, the whole life”.

Hamlet in the opening scene is going to die and in a few seconds he reviews his life in a flashback, knitting the threads of his life, finding symbols, recognizing people, relationships. That flashback makes him so human, so sad, so close to us.

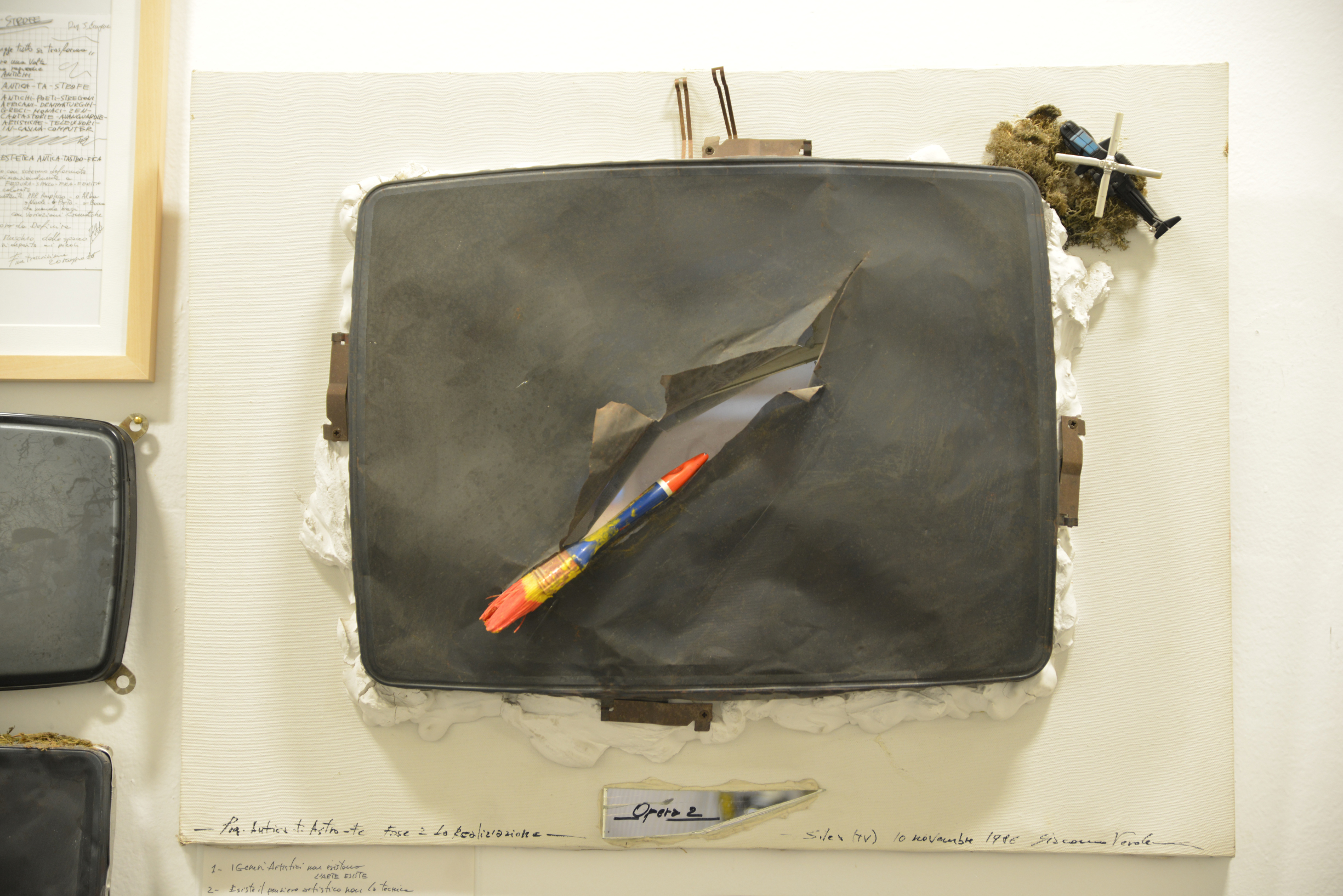

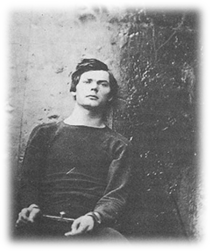

The characteristic of his Hamlet is not the variation of the plot, but the abolition of the plot itself within the more general abolition of time in history. Everything is present simultaneously: past and future. Hamlet is dead and is also going to die, he suffers from a tragedy that has not yet happened: in the compression of the time of history, the entire dramatic action is expressed synthetically in the body of Hamlet, future sacrificial victim: this will be and this has been, as Roland Barthes wrote about the photographic portrait taken by Alexander Gardner to the condemned to death Lewis Payne (1865.)

The beginning is also the end: Peter Brook starts his The Tragedy of Hamlet (2000) with the appearance of the ghost of the father in flesh and blood, a father who wants revenge, a father who knows the consequences of his words. He offers his hand to his son, in a symbolic gesture of birth and embraces him tenderly as for a farewell to death.

“Go to sleep, I won’t die anyway. I just have to find the position.” But Diego has never woken up. It was 3.30 in the night between 13 and 14 March. Two hours later, at half past five in the morning, his wife – a volunteer at the Italian Red Cross- returning to his room, found him dying. Diego, operator of a call center for health service from Bergamo, left us at the age of 46 for coronavirus.

Ophelia and path accidents.

“Doubt thou the stars are fire; Doubt that the sun doth move; Doubt truth to be a liar; But never doubt I love”.

Hamlet will die under the blows of Laertes, the true avenger of the Shakespearean tragedy and will suffer the consequences of the “side effects”: Ophelia become mad because of abandonment and predestined victim of the wickedness of others, she lets herself go to the ultimate encounter with nature by drowning. The machine of history starts moving overwhelming everyone, guilty and innocent. Ophelia’s death is the tragic and painful response to Hamlet’s most excruciating doubt.

The “uncomfortable” deaths are the accidents along the way in the chain of the epidemic: within twenty days from the beginning of the infection, Italy exceeds the threshold of 10,000 infections in Lombardy, the outbreak of the epidemic:

“The mortality data are deepening with the medical records of the deceased: patients who died with coronavirus have an average of over 80 years, 80.3. The average age of the deceased is much higher than the other positive ones. The peak of mortality is between 80-89 years. Lethality, that is the number of deaths among the sick, is higher among those over 80 “(Civil Defense release 8 March, 2020)

The extreme picture caused by the contagion, according to the Scientific Society, «entails not necessarily having to follow a criterion of access to intensive care of the” first come, first served “type” (the first to be assisted is the one who arrives first). In Point 3 of the Recommendations of clinical ethics for admission to intensive treatments, the law states that in exceptional conditions of imbalance between needs and available resources: “It may be necessary to set an age limit on entry to intensive care”.

All the rest is silence

“Do you know what the most dramatic feeling is? See patients die alone, listen to them as they beg you to greet their children and grandchildren. Covid-19 patients enter alone, no relatives can attend and when they are about to leave they sense it. They are lucid, they do not go into narcolepsy. They die in silence “. Francesca Cortellaro, primary physician of the emergency room of the San Carlo Borromeo Hospital.

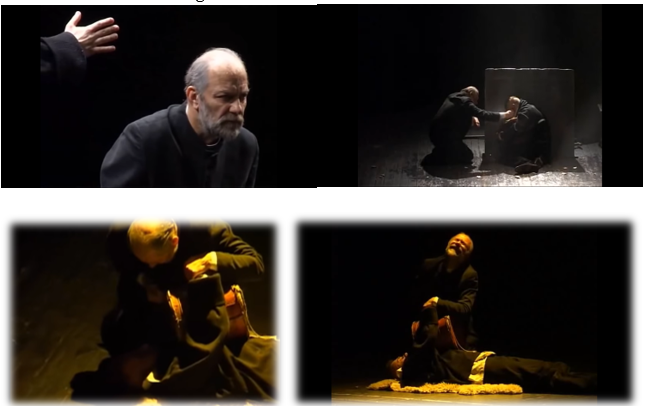

In Nekrosius’ version of Shakespeare’s tragedy (Hamletas, 1997), the powerful image of the ghost of Hamlet’s father appears in two distinct ways: transfigured in the ice chandelier, whose candles placed close together thawed under the eyes of an incredulous, frightened Hamlet; and in the final moment in flesh and blood, contrary to what Shakespeare writes.The truth calls for a vengeance that must be fulfilled, for the ice to completely freeze. And the general atmosphere is glacial and gloomy, the characters go through blocks of ice, Hamlet dies frozen in the stone of pain.

The image of the chandelier is a metal blade that descends from the ceiling on which the drops of ice fall, resounding terribly and vaporizing in the air. It reappears at the moment of the monologue To be or not to be and the blade is joined by a chandelier made of icicles and candles. Hamlet hesitates whether to stay within its perimeter and let the water drops of ice melt with the heat. Take this burden on your shoulders or not? Act, or get out of the circle of assassination that calls for other assassinations? There terribleness associated with this image is given by the urgency: there is no more time, the ice is melting, the candles are wearing out. We need to act now.

Nekrosius eliminates Horace from the final scene; however, does not let Hamlet die alone, and then Latin piètas intervenes. The father who never appeared physically on the scene, enters, hugging him and dragging him away. But first try to instill heat, to make him come back to life as with a heart massage, the precordial punch: the drum that Hamlet has in his womb no longer resounds but the old king tries in every way to make him come back to life. And in the end, helpless in the face of the death of his son, aware of having been the cause of his death, he only has a silent cry.

“One of the two Bergamo patients infected with the coronavirus and transferred to the Bari Polyclinic, died during the transport. The director of the Bari Polyclinic Giovanni Migliore: “He went into cardiac arrest and, despite the maneuvers of the resuscitators made on the landing strip, he died” (Ansa, Bari, 18th March).

Let’s not let him die in vain

In this cruel world breathe with pain to tell my story (Hamlet)

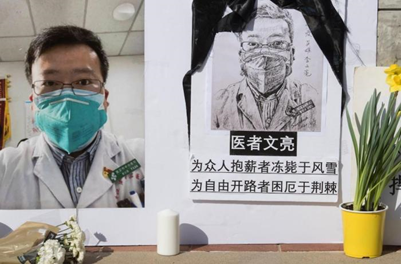

Dr Li Wenliang, who worked as an ophthalmologist in a Wuhan hospital, first revealed the epidemic in a chat in December 2019 by treating seriously ill pneumonia patients (from unknown causes) who had conjunctivitis, but the Wuhan police accused him of spread false news instead of being alert to verify that alarm (they were still in time to stop the contagion).

It took a few weeks for the regime to recognize the existence of the epidemic, clearing them of the charges. Continuing to carry out his activity, the doctor fell ill and died on February 6. The appeal “Let’s not let Li Wen Liang die in vain” is launched. Signatories include Professor Tang Yiming, head of China’s Central China Department of Normal University, located in Wuhan, the center of the epidemic. “If Dr. Li’s words had not been considered unnecessary rumors and if every citizen had the right to tell the truth, perhaps this national disaster would not have occurred, affecting the international community. This appeal calls for respect for the Constitution, which (in theory) guarantees freedom of speech”.

It is asked to set February 6, the day of the doctor’s death, as “Freedom of Speech Day”.