The South African artist William Kentridge is one of the most renowned contemporary visual artists and proposes a poetic view on ancient taste where art and technique come together in the original value and significance of techné: the shows are based on his original filmed animations and recalls those theatres from the beginning of the century that experimented with the rudimental techniques of luminous animation (drawings on pieces of mobile glass, projected thanks to a Magic Lantern), promoting a primitive form of optical art.

William Kentridge’s biography is rich with events and experiences connected to the theatre: he frequented the Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris, he became a set designer, actor and director of the Junction Avenue Theatre Companyand the Handspring Puppet Company in Johannesburg and he put on shows by writers Tom Stoppard and Alfred Jarry; he later became the director of short animation films shot on 16mm as well as an author of drawings and incisions: in their anxious-ridden black comedy where there is a harsh social critique of the South African government before the democratic elections of 1994 in South Africa and before the creation of the Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress, and his pictorial allusions to Goya, Bacon, Grosz and Weimar artists that coexist with the atmospheres of the theatre of the Gran Guignol and Beckett-like dramas.

He worked for Ubu tells the truth (1996-1997), doing drawings and graphics that make up the visual corpus of the successive filmed animations created for the show that went on stage with puppets entitled Ubu and the Commission of the Truth; he then worked on the drawings for the show Faustus in Africa (1995), on the scenes forConfessions of Zeno (2002), on the musical opera The return of Ulysses (1998) from Monteverdi; Preparing the flute on the other hand is a little theatrical model with two animated films in 35mm where Kentridge reinvents his work for the sets of the Magic Flute by Mozart.

|

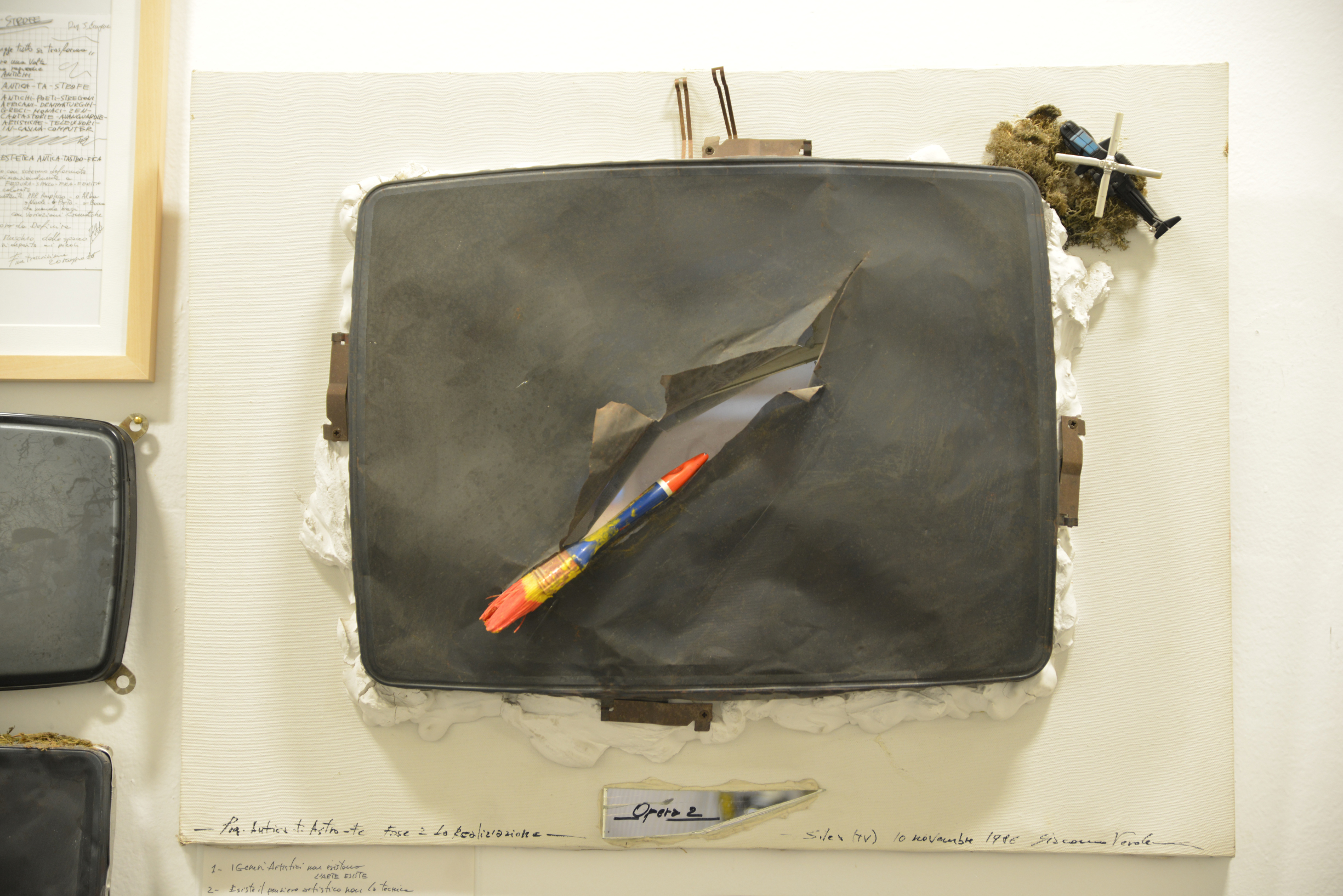

The Drawings for Projections make up the heart of Kentridge’s artistic elaborations and is extended to the theatrical sets: these are animated films and mute films created from carbon drawings and inaugurated at the end of the 80’s with masterpieces such as Monument (1990) based on Beckett’s Catastrophe. His work behind the Boles 16mm is difficult and particular, where he creates animated sequences, without a script or storyboard: the sequence is composed of minimal variations and erasures of a few carbon and monochrome pastel drawings on paper, which conserve the evident traces of their own metamorphosis, an action that goes back to the origins of cinema, the first photographic studies of the Marey and Muybridge movement.

The coffee maker becomes a mine through animation, the stethoscope a telephone: the outside landscape absorbs the dramatic memories and social happenings that it went through; the automation of the medium used by Kentridge counter opposes, according to Rosalind Krauss, the “luck” and free interpretation of the technique that modifies and at times contradicts the conditions and nature of the support: from the flow of images of film to the immobility of drawings.

As Carolyn Christov-Bakargiey recalls, Kentridge has deep interest in different techniques, but does not appreciate the “innovative practices per se, nor the historical evolutions of art, style and technique and prefers obsolesce”, and underlines the deep meaning of this open modality, expanded and processed through the recording of the drawing for its projection, which contains the imperfections but also the layers of memory, against the “dulling” of society: “In his art an erasure – counter opposed to the distinct lines – is also a healthy metaphor for the protest against certainty and preconceptions at the base of human and social relationships in the world that only appears to be more interactive and democratic than the digital era. The erasure puts into questions any definitive affirmation that is possible”.

Kentridge talks about a pre-cinematographic technique or rather, a “cinematography of the stone age”, and the criticRosalind Krauss underlines the “reinvention of the cinematographic medium” through the re-writing of a new linguistic code and the recuperation of a craft-like practice that was lost forever in the era of computerized programming: Kentridge, although he uses the technique of stop-motion animation that records the phases of drawing, “does not pursue the cinema as such but instead builds a new medium on the technical support of a common cinematic practice of mass culture”. In other words, according to Krauss, Kentridge’s animations would be more similar to a flicker book, to a rotating cylinder of a Phenakistoscope, the taumatrope, in other words those instruments that are obsolete today and that primitively and rudimentally anticipated the recording of images in motion

|

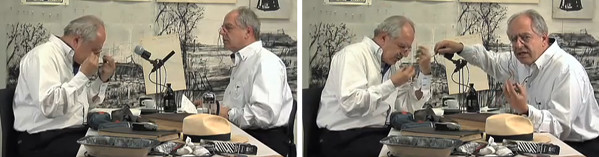

This is Kentridge’s direct testimony: “the technique that I take on to make these films is primitive. Traditional animation takes thousands of different drawings that are recorded in sequence to make a film. This generally implies the work of a team of animators and consequently the fact that the whole film must be projected beforehand. The images are drawn by the main animator and the intermediate phases are completed by the assistant animators, whereas the others work on going over lines and colouring. The technique I use consists of a sheet of paper stuck to a wall in a studio, I put in the camera in the middle of the room, usually an old Bolex. I sketch a drawing on a sheet of paper and then I go to the camera, I take one or two frames, I (marginally) modify the drawing, I go back to the camera then to the drawing, then to the camera and so on. In this way every sequence, compared to every frame of the film, is one unique drawing. In all there will be about 20 drawings per film instead of the thousands that you would expect. It’s a similar procedure to doing a drawing, more than to doing a film. Once the film has been elaborated by the camera, the completion, the editing, is the addition of sound, music and the rest works as for any other film”.

The graphic and film works of William Kentridge cannot be separated from the recent political struggles of South Africa, the theme of the Apartheid which he dedicates a long saga to, Soho Eckstein, the story of a greedy and cynical capitalist who is a symbol of the corruption and depravation of Johannesburg that is under pressure from constant racial injustice and the exploitation of workers in mines. A character that is opposed to Soho Eckstein is the solitary and sad Felix Teitlebaum. History of the Main Complaint was created in 1995, Felix in Exile, in 1994, the year of the first democratic elections in South Africa.

When Kentridge is asked to collaborate in the form of a exhibition on his incisions made for the graphical series Ubu tells the truth he adds a naked human figure as a narrative element placed inside the white profile of a shapeless mass of King Ubu who takes all the forms of power, with his pointed head and his spiral stomach on the black-slate background of a blackboard. Ubu, the emblem of institutionalised cruelty becomes the “grey area” inside us and the system (“The structure” as Julian Beck would have said…) which we are responsible for. These drawings and these incisions have become the central nucleus of animation for the show Ubu and the commission of the truth in collaboration with the Handspring Puppet Company (1995); it is a violent protest against the events and racial conflicts of South Africa before the elections.

The animation technique in this case, compared to the experimental mode of the other drawing for projection on Soho Eckstein, is different as it enriches the rudimental cut outs of newspapers, the processions of dark silhouettes like glued-on shadows and metallic parts onto paper, white chalk drawings on dark paper and films of other archive material that are a testimony to the violence and repression, as well as that of the police armed with whips that attacks the crowd in Cato Manor in 1960 or attacks a group of students at Witz University during a state of emergency in 1980 and that of the revolt in Soweto in 1976. The theatrical viewpoint began from the disturbing revelations that came out of the courts of the Commissions for the enquiry into the truth and reconciliation of South Africa. The Commission was created with the purpose of recording the witnesses of the horrors, the abuse and violations of human rights.

|

Woyzeck on the Highveld

Even William Kentridge works on Woyzeck as Robert Wilson had done in the Theatre (with music by Tom Waits) and William Herzog in the cinema with Klaus Kinski in 1979; the drama was written by Buchner in 1837 and was incomplete because of the death of the author, and so is a fragmented text, as it has been defined, in “stations”. It talks of the unhappy story of the soldier Franz Woyzeck, who dies humble jobs to support his companion Marie and their son who has not yet been baptised. To make more money he does everything for the captain and is a human guinea pig for a doctor for some experiments; Marie betrays him. Woyzeck finds Marie had his rival at a dance in a tavern, and madness and hallucinations bring him to kill the woman.

Kentridge had put on Buchner’s Woyzeck in 1992; in the program notes of the show Kentridge wrote that he was close to this drama as he had seen it as an emblem of conflict (social, political and emotional) after a show in the 70’s and since then he tired to imagine a different context from that of Prussia of the 19th century.

The new context could be none other than the South Africa of today. The second aspect that pushed him to the representation was the desire to work with the company Handspring Puppet Company in a mixed performance where the drawing could be united with the general frame of the representation where the actors were taken away and replaced by puppets where other ways to transmit the emotional depth where not guided by the face of the actor. The third reason was the desire to put an animated film onto the stage that would have a dynamic rapport with the movement of the puppets on stage and that would update the ancient culture of the theatre of figures and the shadow theatre.

Today’s work seen at the Eliseo Theatre during the Romaeuropa festival kept an extraordinary force thanks to the presence of the wooden puppets of human proportions that were guided efficiently by stagehands that were not wearing hoods that awaken an ancient curiosity, and the able animated work of Kentridge.

|

This takes us, without words, into Woyzeck’s head, exploited, overwhelmed, offended, persecuted by the powerful and betrayed, he who thinks differently, who is the emblem of the persecuted and the humble ill-treated man who at the end succumbs to his own nightmares, goes mad and kills the woman he loves as a definitive act of self annihilation and rebellion. Woyzeck’s mind races between objects, processions of shadows and desires that are not expressed, dreams, psychological disturbances, and enchanting wonders. The sky is a forest of stars and is the only ray of light in an impossible happiness. The technique Kentridge uses is extraordinary as is that of the stagehands of the puppets: in both cases the hand that gives the soul tot eh object. The spectator can be considered the sum of the artistic work of William Kentridge, also because of the theme that is dealt with, that has the South African Apartheid as its foundation.